Notes from Helsinki

Forests, books, and interfaith encounters, a combination that gets you thinking

Uriya Shavit

Many years ago, so many that I can’t remember the name of the channel or the program, I watched a documentary about Finland. The camera jumped between dozens of faces on the streets of Helsinki and the anchor asked what they had in common. Then came his answer: No one is smiling.

Which is why I was surprised to learn in March that Finland was ranked for the fifth consecutive time as the happiest nation on earth in the annual UN-sponsored index. The index surveys subjective accounts of well-being as well as more objectively comparable data such as GDP, personal freedoms, and levels of corruption. Israel was ranked ninth, the United States sixteenth.

Not a small achievement for an icy country that in the sixties and seventies was struggling to maintain its independence under the threat of Soviet aggression and witnessed massive waves of emigration to Sweden, and, in the late 1980s, suffered a devastating economic meltdown.

I am here for several weeks, teaching a class on the sociology of religious law at Helsinki University.

At some point, I dare and ask my students if they are indeed the happiest.

One says a better definition would be that they are the “most not not-happy nation on earth,” implying that Finns mastered the art of being satisfied with what they have and are realistic in their expectations.

Another says that “privileged” is a better definition: They are part of a welfare society like no other in the world that affords them a strong sense of solidarity and security.

I haven’t figured out if Finns are the happiest. But they certainly have good reasons to feel relaxed.

I arrived in this land of innumerable lakes and forests from what was the hottest, noisiest, and most crowded summer in the history of Tel Aviv, a city turned construction site, and am cherishing the ability to hike for over an hour in the woods, in the heart of the capital city, without hearing a human voice.

Within four decades, the population of Israel approximately tripled while the territories under its control shrunk by more than two-thirds. Experiencing the vastness of space in the Finnish capital, one can’t help but wonder whether the real existential threat Zionism faces is, in fact, ecological.

At the residence of the energetic Israeli ambassador, Hagit Ben-Yaakov, I meet with local Jewish and Muslim leaders to discuss with them their understandings of antisemitism and anti-Muslim articulations. The Moroccan ambassador is also present.

One great irony of our times is that the fate of Jewish freedoms in Europe has become intertwined with that of Muslim freedoms.

The Jewish and the Muslim leaders expressed grave concerns regarding soon-to-pass legislation that would ban Kosher and Halal butchering, and about the possibility that circumcisions would be next.

They do not think racism as such is the motivation for the prospective bans; rather, they argue that the bans are driven by a patronizing pretense to educate minorities about progress and the gross hypocrisy of keen hunters.

I may add that before targeting Kosher and Halal butchering, Finns would be well advised to delegalize the torture of doves, roasters, and horses (let alone of adults) in the circus.

There is no better time to read than on sojourns. At the shore of the Helsinki harbor, I have with me a recently published and elegantly written book by Israeli journalist and author Igal Sarna, “A House in Portugal.”

It documents Sarna’s relocation and retirement in a small, tranquil Portuguese town, where an Israeli can buy and renovate a spacious, picturesque house for a sum that covers several years of rent in Tel Aviv. Just.

The phenomenon is likely to grow. The hi-tech industry made Israel the economic success it is but also made it one of the most expensive countries on earth. For some Israelis, those not in hi-tech, it became too expensive.

With cheap flights and advanced media helping obliterate the meaning of distance, more retirees are bound to reduce Israel to their emotional and cultural homeland while finding a home someplace else, living off their Israeli-earned pensions.

At a beautiful lake resort in the suburbs of Helsinki, I speak to young activists from Nordic Christian Democratic parties. The topic of their retreat: Sustainable Migration.

I ask them what it means to be a Christian Democrat in the 21st century. Is Christian creed their reference and guide for politics? Can there be Christian Democracy without Christianity?

A veteran member of parliament joins, and a generational gap is revealed. What seems obvious to him seems far less certain to the younger activists.

The trees in Finnish Lapland change their color this time of year to majestic gold, red, and yellow, as if crowning the lakes which they surround. It is a long train ride from Helsinki, as many as 12 hours.

Coincidently, I have with me only two things to read. One is Haim Be’er’s novel, “The Time of Trimming,” which, already in the mid-1980s, pondered whether Israeli Orthodoxy can still chart a religious alternative to messianism and anti-Zionism.

The other is the supplement of Hamodia, the daily newspaper of Hassidic Jews (don’t ask, long story). There, the enraged columnist M. Eliraz explains in length why human-made laws lack moral authority and why the Israeli judiciary is a big lie.

Soon Israelis will go to the polls, once again. Voters are in conflict about many issues.

Yet one alarming fact is conveniently overlooked. At this point in time, the best predictor of how an Israeli Jew will vote is not country of origin, profession, education, or income, but the level of religiosity.

Is a religious war in progress and we fool ourselves that the divide is about an individual?

Helsinki is home to some 2,000 Jews, several dozens of them Israeli. The community is rooted mainly in the settlement of veteran imperial Russian soldiers. It operates a synagogue, a cultural center, and an elementary school (up to the eighth grade), attended by around eighty pupils. The language of instruction is Finnish.

The synagogue has a small library that includes hundreds of books in Hebrew. Some fifteen community members use its services. On the wall, a framed picture of Eliezer Ben Yehuda overlooks the richness his project made possible. He would have been pleased.

I once saw Amos Oz, aging and having won almost every literary prize possible, return to the authors’ table in Rabin Square at the annual book fair, proclaiming, beamingly and proudly, that he had just autographed some forty copies. The ego of writers.

If my memory doesn’t fail me, it is in “Tale of Love and Darkness” that Oz wrote about the comfort authors take in knowing that even if all would be lost, one copy of their works would somehow survive.

Shamelessly I search whether any of my own made it to the abundant Helsinki synagogue library. I locate my first novel, “The Dead Man,” on one of the shelves. I feel alive.

It has become common knowledge that education in Finland is the best in the world. Why is it, then, that Israel, not Finland, is Start-Up Nation?

After a few weeks of teaching here, I start to wonder whether some of the core flaws of Israeli education – the chaos, the every-child-is-a king and scandal or festival mentalities, the cruciality of extra-curricular programs – are more advantageous for innovation than a culture of moderation, egalitarianism and guarantees.

But perhaps this is not so; perhaps the proper question to ask is what could have become of Israel if it had a functioning, modern education system, compulsory for all.

At the Helsinki “Museum for Contemporary Art,” overlooking the parliament building, it comes back to me: I have already been here, twenty years ago, trying to kill time before an interview with a member of parliament, and almost stepped on cans of Coke which turned out to be an installation.

Two decades have passed, and the museum is still largely a collection of uninspiring and pretentious political statements.

One hall features the inscription “No War” on a white wall, which can also be seen from the outside. It is explained that the hall was to exhibit an installation by Russian artist Evgeny Antufiev, who withdrew it once the war in Ukraine began. Instead, an anti-war message was installed.

It is not for me to judge Antufiev, but there is no courage in “opposing wars.” No more than there is virtue in being against poverty and depravation. Evil always has a name. Call it by its name, or else you support it.

There are Ukraine flags everywhere in Helsinki, including on the iconic building of the main train station. A century of Russian occupation and half a century of Russian intimidation left no sympathy for Russia among Finns.

The majority of men are conscripted for up to one year of service. There is pride in serving. Soon the European country with the longest border with Russia, and a very capable fighting force, will join NATO. Perhaps, the most embarrassing of Putin’s many miscalculations.

The journey to Tallinn by ferry takes two hours. Grey clouds almost fuse with the blue Baltic water.

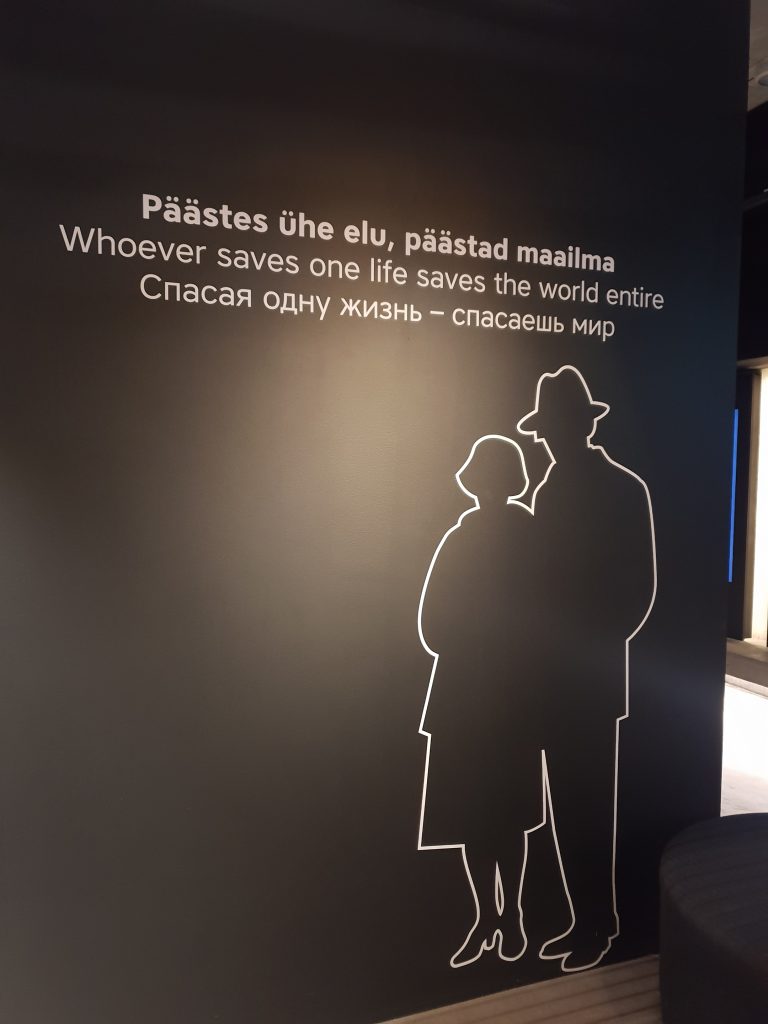

The Estonian capital’s “Museum of Occupations and Freedom” tells of persecutions, tortures, and deportations, a lost generation under Soviet rule. And then liberty, at last. An inscription on one of the walls reads in big letters: “Whoever saves one life, saves the world entire.”

On a beach shore in Tel Aviv, where people leave books that they no longer desire, I found one recent summer day a forgotten novel by Dan Tsalka from 1982, “Gloves.” Tsalka was born in Warsaw in 1936 and made Aliyah in 1957.

The book describes the boxing scene of Tel Aviv in the 1930s and the Polish olim who dominated it. I saved it for the right occasion and am reading it on the ferry back to Helsinki.

The young boxers depicted by Tsalka seem to care only about sports and the opposite sex. They are blind to the catastrophes that await them and their families.

I can’t help thinking what the late Tsalka would have thought had he seen his fictitious 1930s olim punching above their weight in the autumn of 2022, here, in Baltic waters, somewhere between Estonia and Finland.

Books wander in wondrous ways. As do people.