Shoah and Popcorn

The 2024 film scene was dominated by movies dealing with the memory of the Holocaust, reinforcing the problematics of the Shoah and its aftermath being remembered through cinematic images, including cynically commercialized ones.

The Report hosted a special panel discussion about the thin lines between memory and distortion, featuring Prof. (emeritus) Moshe Zuckerman, Tel Aviv University, a scholar in the philosophy of ideas and science, Dr. Shmulik Duvdevani, the movie critic of Ynet and lecturer in cinema at Tel Aviv University, Prof. Giacomo Lichtner, Victoria University of Wellington, expert on Holocaust cinema, and Prof. Uriya Shavit, Tel Aviv University, Head of the Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry and the Irwin Cotler Institute for Democracy, Human Rights and Justice

Prof. Shavit: I’d like us to start with three or four of the main critical arguments that have been made about Holocaust movies. Moviemakers, and not just commercial ones, often have the inclination to end up with a happy ending or at least some kind of positive message. It’s almost inescapable. I think it was Stanley Kubrick who said that the problem with Schindler’s List (1993) is that it deals with six hundred Jews who were saved, whereas the Holocaust is about six million Jews who were murdered.

Think of the Oscar-winning Hungarian film Son of Saul (2015), which is known as the harshest and bluntest Holocaust movie. In the end, at least the way I understood it, it also finishes with a positive tone.

Dr. Duvdevani: First of all, I’m not sure that cinema, in general, aims to please the audience. It depends on which films, where they are made, and what they are dealing with. Although Kubrick is one of my favorite filmmakers, I’m not so sure that I agree with his comment about Schindler’s List. There’s a lot to say about Schindler’s List, but I’m not sure the main argument against the film is that it deals with the survival of Jews and not the extermination of Jews.

We should bear in mind that Kubrick himself wanted to make a film about the Holocaust called “The Aryan Papers.” He already had a screenplay, and once he heard that Steven Spielberg was making Schindler’s List, he decided to set this project aside, although I don’t know why. He and Spielberg were very good friends. They remained so even after he made that comment.

But I’m not sure that, in general, Holocaust films are about happy endings. For example, Son of Saul ends with the death of the protagonist, and it deals with many ethical questions regarding the representation of the Holocaust.

Even in films with a so-called happy ending, much of what is happening until the end is tragic. These are not feel-good movies.

I think the most important question is not how movies deal with the Holocaust narratively, but how they deal with it ethically and aesthetically.

Prof. Zuckerman: On a more personal note, I’m the son of an Auschwitz survivor, so I can say that the Holocaust has contaminated my life from the very beginning. At home, we dealt with the Holocaust right from the beginning. We are one of those families who were talking about the Holocaust all the time. Dealing with it from the very first moment of my existence has devastated my life.

This is why, in the first part of my life, I watched many documentaries and movies made about the Holocaust and gained a lot of knowledge, so to speak, about the Holocaust, including from the artistic works about it.

But I’m approaching this academically from the Frankfurt School of thought, and this is the more profound thing I want to say about the issue you just raised. There is one very famous saying from the end of the 1940s and the beginning of the 1950s by Theodor Adorno: “After Auschwitz, to write a poem is barbaric.”

Another person not talking about the Holocaust directly, but talking about Nazism and aesthetics, was Bertolt Brecht. In his poem “A Bad Time for Poetry,” he says there are two forces fighting in him: the beauty of the blooming apple tree and the presentation of the painter. The painter being Hitler, of course. And Brecht said only the painter is pushing him to write.

There are times when aestheticism is not a proper means to deal with reality. Adorno later took back his saying against writing poems after the Holocaust after he read Paul Celan’s “Todesfuge.” What Adorno said then was that we should not think that after Auschwitz, everything done aesthetically is barbaric just because culture has joined barbarity. Yet he also emphasized that suffering has to be represented in a way that gives the one who is tortured the right to scream, and thus, the role of art is to make suffering more presentable to people.

Of course, the question was how to do that. Adorno presented the ethical question of the extent to which art is able to represent reality, and that goes not only for the Holocaust. In the end, whether a direct or indirect reflection of reality, art is a representation and not the reality itself. I am reminded of Magritte’s painting where the pipe on the canvas is, of course, not a real pipe.

Going back to what Uriya said, Adorno said that every kind of work of art, even if it’s dealing with the most unpleasant things and is dissonant or even ugly, every kind is something from which you gain some kind of pleasure. This is one thing that got me to think about the fact that in most of the films I saw about the Holocaust, the audience gained some kind of pleasure. And you cannot deal with the Holocaust this way. You should not.

If you remember, there was a shower scene in Schindler’s List. When I saw it, I kept thinking that I knew that scene from somewhere. Where did I know this combination of shower and horror? All of a sudden, I remembered Psycho by Hitchcock, in which we have that shower scene. Then I compared some of the images that Spielberg used to those used by Hitchcock, and I was horrified to see that Hollywood had struck again.

Schindler’s List had a “Hollywoodian” way of doing it. I’m talking about the suspense moment: whether the shower will be lethal or not. I don’t need that in learning about the Holocaust, in a movie about the Holocaust. I know how things ended. So yes, the thing about gaining some pleasure, whether it’s a suspense pleasure or an aesthetic pleasure, seems to me one thing that most of the Holocaust movies were permitting.

Prof. Lichtner: I agree with Shmulik that I’m not sure that a film, in general, has to please its audience. I think the problem is more that historical cinema has to provide an experience that audiences can relate to; that’s where the problem arises. The problematic of Holocaust movies is the pursuit of empathy that actually can only deliver the illusion of empathy.

This is where the shower scene from Schindler’s List comes in very neatly because it’s a scene that’s shot in constantly shifting perspectives. So, it’s designed to give the audience the experience of being in a shower that could be a gas chamber, but also of surviving it. That’s something that actually quite a few representations of gas chambers have done in recent years, and I agree that that’s ethically very problematic.

Regarding endings, particularly, filmmakers are clearly aware of the expectations for positive endings, and there are quite a few examples of films that try to deal with it by giving you at least two endings. One egregious example is Life is Beautiful (1997). I remember watching it as a 20-year-old when it first came out. It gives you an evocative ending with the off-screen death of the protagonist, but then it has to give you the happy ending the audience wants.

There are quite a few other examples, but there’s a film that came out immediately after Life is Beautiful called Train of Life by Radu Mihăileanu (1998). It is not as well-known, but it is wonderful. It also has a double ending, but the endings are reversed, so the happy ending comes first, and the real ending comes second. That order makes all the difference. My point is that it matters in which order you put the endings.

Prof. Zuckerman: Like what you just said, Giacomo, I think there is a structural problem, ethics-wise, that begins with our definition of the Holocaust. What is the Holocaust? Is it a series of dramatic moments and events, or is it, as some have understood it, “the chasm of civilization,” meaning that it is not an event that you can grasp through the order of a summary of events?

We have to understand the Holocaust as something that industrialized an annihilation of men, being bureaucratically performed and administratively directed according to ideology. Right from the beginning, it made men fungible.

The question is: can a movie, which is an art form that relies on pictures and on narratives, cope with representing what happened?

I can hardly imagine that intellectual writing is able to cope with the Holocaust. I’m sure that cinema is not able to do that.

Prof. Lichtner: I completely agree. Some of the essential parts of what makes the Holocaust what it is, things like dehumanization, are also some of the hardest to represent.

I want to be provocative and say that maybe because of what you said, Moshe, about the intellectual discourse and its limitations, maybe we have to think that sometimes only cinema or only art in general can actually get close to describing the Holocaust because of their power to evoke without describing, without trying to understand and explain. It depends on the case, but I don’t think cinema is intrinsically less capable than other forms of language.

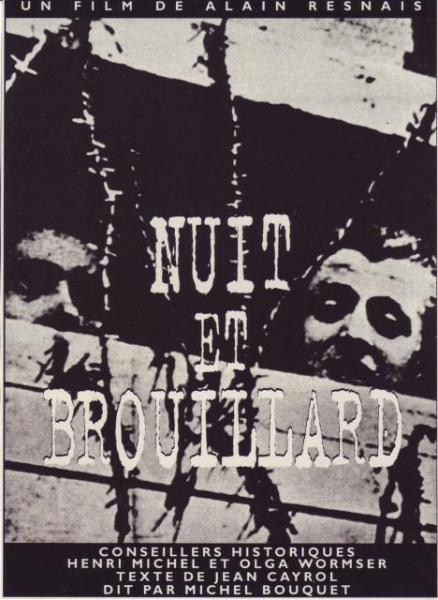

Dr. Duvdevani: I completely agree with Giacomo because I think two of the films I find the most important and that are the most profound in dealing with the Holocaust are actually documentaries, Night and Fog by Alain Resnais (1956) and Shoah by Claude Lanzmann (1985), and, by the way, Lanzmann could have never made Shoah had it not been for Resnais. I think these films actually deal with two major issues: image and testimony.

First, the issue of the image: what images can you show when you are dealing with the Holocaust, with death, with the extermination camps?

Secondly, Shoah, especially, deals with the crisis of testimony, which is exactly what the Holocaust caused. Giorgio Agamben, the Italian philosopher, speaks a lot about it. Primo Levi writes a lot about it.

Prof. Shavit: I want to continue from here and discuss the second main criticism about Holocaust movies. Generally, the argument is that it’s good that so many movies about the Holocaust are produced because they ensure that people will never forget and that they will learn from history.

So, three points on this. First, the Holocaust never made it into popular culture before 1978, with the miniseries Holocaust: The Story of the Family Weiss, which aired first on primetime American television and then on German, European at large, and Israeli television.

Yet I’m not sure that people in the 1960s and the 1970s knew about the Holocaust less than they know today, and I’m not sure the lessons of the Holocaust were less profoundly ingrained in public minds in the 1970s and the 1980s than they were in the 1990s and the 2000s, after the Holocaust became so big in our culture. The genocide in Rwanda took place well after Family Weiss and other movies were watched by tens of millions of Americans, and that didn’t exactly motivate the United States to intervene.

The second point is that, in the end, anything you do in cinema is fiction. Even documentaries are a form of fiction. There is an unavoidable problem, which is that movies about the Holocaust turn the Holocaust into fiction. This is simply inescapable.

The third issue takes me to a personal experience. I was in Auschwitz just once, and at a very late age, not as a school kid or as a soldier.

The thing I took from there is that if I was a Holocaust denier, nothing I saw in Auschwitz would convince me otherwise.

So, the problem with Holocaust denial is not so much about knowledge but about whether you accept the confirmed sources of knowledge in our day and age. If you don’t, if you think everything school and other establishments teach you is part of one big conspiracy, is a bunch of lies, then even watching fifteen Holocaust movies with graphic depictions from extermination camps will not change your mind.

I think it’s also important to note that Lanzmann’s Shoah was far more effective in teaching people about the Holocaust than Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. There is no footage from the actual Holocaust there. It’s people testifying. Maybe this idea that we need the visual to be convinced that something really happened and to immerse it within our souls and minds is a myth.

Prof. Lichtner: It’s a big question and an important one. I’m going to continue from my last comment about the potential, the promise of cinema. I’m going to defend the idea that just because all films are fictional, that does not automatically turn the Holocaust when represented in movies into fiction.

The relationship between truth and fiction is complex, and different films handle it in different ways. The American historian Robert Rosenstone talks about true invention and false invention. It’s a problematic dichotomy, in my view, but it’s useful for us in terms of thinking about the role that invention, that inaccuracy, can have in cinematic constructions of historical arguments.

In principle, I think invention is a tool. It’s a tool to maybe encourage people to learn or to find out more. Sometimes, I think it is a tool to teach.

I love Shoah. I worked on it a lot quite a few years ago. True, it doesn’t use documentary footage, but it certainly uses artifice and invention. There are a couple of moments that I’m going to pick out. One is the use of point-of-view camera work. Putting the camera on the front of the van as it drives through the forest puts you in the driver’s seat of a gas van, in theory. So, Lanzmann did not find footage of a gas van from 1942 or 1943; instead, he used creative reconstruction.

The second moment is the one that’s perhaps best known. It is with survivor Abraham Bomba, who did not speak to Lanzmann in the way that Lanzmann wanted him to. Bomba, the barber from Treblinka, would not relive the trauma. So, Lanzmann interviewed Bomba in New York, he interviewed him elsewhere, and in order to get him to relive the trauma, he brought him back to Tel Aviv. He put Bomba in a barber shop, and he got him to reenact the cutting of hair.

It is one of those moments that are very abusive. But it’s one of those moments that makes audiences break through, not so much to understand the experience, but to understand that you can’t understand it. And that’s a crucial step.

Prof. Zuckerman: Uriya, I would like to refer to two of your arguments. The first one: There was an incident right after Schindler’s List featured back in 1995, where a group of black youngsters was roaring in laughter every time they saw an atrocity on the screen, and people thought that it was antisemitic or black antisemitism, which was very curious because, in the 1960s, Jews and blacks used to work together in order to fight for human rights.

Then, some historians and psychologists interviewed those young black men, and it turned out that their laughter when watching the movie had nothing to do with the Holocaust and nothing to do with antisemitism. They had thought it was an action movie.

For them, it was an action movie, and this goes back to what I said from the beginning. The moment that you want to represent one of the most unspeakable and unrepresentable things in human history with the means of the culture industry, you end up with just that – with people saying, it’s an action movie!

A member of my family who lives in America was on the actual Schindler’s list; he was in the Holocaust. I want to affirm what you said, Uriya. After the movie was released, he was invited to a lot of roundtables and a lot of panels to discuss his experiences. I remember he came to Israel and showed us one of the invitations to a roundtable, where I could see it read: “You’ve seen the movie; now come and see a survivor.”

I was completely shocked and asked him if he really let them do that to him. And he asked me: “What’s the problem? This is the way that we can pass on what happened in the Holocaust!”

I have to say that I did a little survey among Holocaust survivors, not something that I could scientifically present. Some of them said it was good that the movie was done because what happened to them was similar to what was shown in the movie. But it was very few of them. Some said, what are you talking about? What does Schindler’s List have to do with the Holocaust?

And the vast majority said they don’t care about movies. You can’t grasp the Holocaust by watching movies, they said. This is what the vast majority of the Holocaust survivors I spoke with told me.

I had to take it seriously because I understand one thing, and I’ll say it in terms of Walter Benjamin, who asked himself back in the 1930s how we could go about the fact that art had become so abstract that we are losing the masses. We are losing the audience. He said we have to find a way to include some kind of kitsch to win over the hearts of the people. He said that the only medium in art that was able to do that, taking all the kitsch of the 19th century and putting it into modern terms, is cinema.

And this, of course, brings us to the question of whether movies are indeed able to do it. But not by representing reality; by doing something that you called fiction, but not in the bad sense, in the positive sense.

Art is always representation. Art is never reality. It is always a representation of reality as if it was reality. To fictionalize reality in that way means that you have to produce something that is able to win over the people without losing the message. If you win over the people, who indulge in the kitsch and the happy endings we are talking about, we are losing the one thing we intended to do, the information and the values we intended to convey.

By the way, Shmulik, you are right in what you said that this is a crisis generally, but on the other hand, I think the only way that you can deal with it is not by giving up and providing an artificial narrative but by letting the people talk. For Lanzmann, it took being a little bit postmodern and many perspectives in a documentary, but Shoah has become one of the most important films.

Prof. Shavit: The problem is that although fiction is never reality, most people see most of reality through fiction. That’s a reality we cannot change. I have to share with you, Moshe, that my Schindler’s List experience was not as horrific as yours, but the fact that it’s vivid in my head after so many years, well, I think it is telling.

I was watching it at the Ayalon Mall in Ramat Gan, and behind us sat a young person with popcorn and a Pesek Zman waffle bar, and during the break, I remember him telling his friend while sucking on the popcorn and the Pesek Zman what a difficult movie it was to watch. And I still have this so vivid in my head.

Dr. Duvdevani: I want to refer to some of your assumptions. First of all, regarding the TV series about the Weiss family, by the way, with the young Meryl Streep. Anton Kaes, professor of cultural studies at Berkley, expressed concern that Americans would think that the Holocaust looked exactly like its representation in that series, that the series’ narrative would become the main narrative of the Holocaust for millions of Americans. Well, I don’t think millions of people actually think the Holocaust is exactly like what you see in a movie.

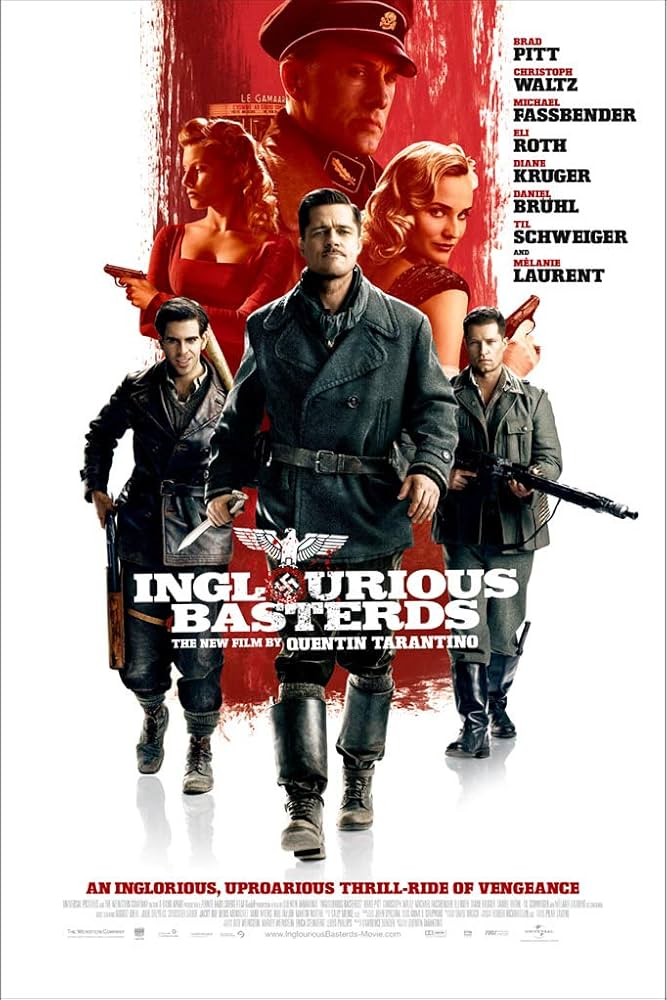

I can just give an example. Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds (2009) implied that the Holocaust of the Hungarian Jews never occurred because Hitler was murdered in a theater before that, before June 1944. Well, I don’t think that people who see Quentin Tarantino’s film actually think that that’s the way Hitler died, and that’s the way the war ended, and that nothing happened in Hungary. They will understand the film just as Tarantino wanted them to understand it: as a film that is historical fantasy. Let’s fantasize that Hitler was murdered, and that would be a “happy end.” The kind of happy end that you are talking against, Uriya. But Tarantino was doing it very intelligently, knowing what cinema is capable of doing when dealing with history.

Now, I completely agree that Lanzmann’s Shoah is a much more appropriate text than Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List.

There was a film, a horrible film, called The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (2008). I still have goosebumps when thinking about it. The kid of the Nazi commander of the camp is going to the gas chambers along with his little Jewish friend. Okay, what are you saying here, that Nazis were exterminated in the gas chambers?

Yet there is one thing we should bear in mind: that many more people watched Spielberg’s film than watched Shoah. Let’s be frank about it. Not many people around the world actually watched Lanzmann’s Shoah, and most of them were highly educated.

Pauline Kael was a very important film critic for The New Yorker, and she was the only one who “dared” to write a bad review of Shoah. She said it was too long. You have to take into account how many people actually watched it when considering its contribution to the memory of the Holocaust, to the learning of its lessons.

Prof. Zuckerman: I would like to go back to Uriya’s question. What do people learn from Schindler’s List? Before having seen it, what did they know about the Shoah?

In Germany, one thing that was criticized was not that the Nazi was the hero, but that a capitalist Nazi was. I just said that any kind of art is always some kind of fantasy because it is some kind of illusion. The question you need to ask about Tarantino is: what is the point of the fantasy? What does it actually say? How appropriate is it in context?

Prof. Shavit: Perhaps, Moshe, we can say that if Oskar Schindler is also part of the story of the Holocaust, and that there were also good Germans, the problem with Schindler’s List is that it became the Holocaust movie. It’s shown to school children, and they, including German school children, think they learn about the Holocaust, not about a minor aspect of the Holocaust.

Dr. Duvdevani: I think this is the problem. The problem is not the movie. The problem is what teachers, for example, are making of that film, especially if this is the only one they have pupils watch.

Prof. Shavit: Yes, but Spielberg was Spielberg already when he directed Schindler’s List, and he could have chosen a different project. He knew he was making the Holocaust movie by merit of him being Spielberg.

Prof. Zuckerman: Before we move on, I want to say I remember that I was a sociologist in the Israeli Air Force when the Holocaust TV series about the Weiss family aired, and I had the opportunity, being a sociologist in the military, to have my people do research with soldiers by command. You know, if you are a sociologist and can question people by command, they have to cooperate.

I had a group of some thirty people. There was only one television channel in those days, and everyone watched the miniseries about the Weiss family, and I got to ask the young soldiers what they thought of it.

I will never forget the one young officer who stood up and said to me it was a very good thing that we watched the series on TV because it connected him emotionally to the Holocaust.

At first, I really thought, well, the culture industry is effective. He was connected emotionally! It took me two days to be troubled. What did he mean by “emotionally connected to the Holocaust?” What does it say about your personal emotional need to have some kind of catharsis? What does it mean in relation to the real historical event?

And I have to admit that for many people, the way they engaged with Schindler’s List was not a means of coping with the Holocaust but a means of having some kind of catharsis.

And I think that the Holocaust is the one thing that you should not have catharsis through. I think that you always have to have a very tension-filled relation to it.

Prof. Shavit: That actually brings us perfectly to the third point of criticism, which I am very curious what Giacomo would have to say about. It is, in a word, the cynicism of it all.

I want to make the following point: I have a suspicion that the reason why we have so many movies about the Holocaust is not because of the complexity of the topic, the challenges the topic involves, or the importance of the topic. Rather, it is because of two cynical considerations.

One, the Holocaust is perhaps the only major historical-political issue about which there is still consensus, at least within the mainstreams of Western societies. So, it’s the safest serious subject to deal with in an age when everything else has become so controversial.

The other thing, which is even more cynical, and here, Roberto Benigni and Spielberg enter, is that it wins you those awards. For some reason, despite the fact that, well, at least I think these awards are largely meaningless, movie directors and actors are so keen to win Oscars and other trophies. And the thinking, at least subconsciously, is: let’s do one about the Holocaust and get recognition as classy, serious, deep directors or actors!

I think the most deplorable moment in the history of Hollywood, and there are so many of them, is Roberto Benigni jumping on those chairs and being so outrageously happy without taking even the slightest second to think how inappropriate all of this is given the subject matter of Life is Beautiful.

Now, to be clear, Spielberg never actually thanked the six million when he won his Oscar. If you hear what he actually said, he wasn’t explicitly thanking the six million. But the fact that so many people remember that he thanked the six million has to do with his speech, that moment he waited for so long, looking as if he was thinking about the people he wanted to thank for helping him with the movie and his career and the six million in the same breath. Oh, boy!

Prof. Lichtner: There’s an episode in Ricky Gervais’ Extras where Kate Winslet plays an actress who’s playing a nun in a Holocaust movie, and she expresses this cynicism on set wonderfully. She says: “Oh, look, I’ve done Titanic, if I don’t win an Oscar with this one…”

Today, the thing that makes a film popular is to make a Holocaust movie and then say that it wasn’t about the Holocaust. We see it with Zone of Interest (2023), and in fairness, it’s been done for some time now. Alain Resnais said that Night and Fog was never about the Holocaust, but was always about Algeria, which is blatantly not true. So, of course, there is a commercial calculation there. Why shouldn’t there be? Cinema is a commercial medium, and it has to sell.

Prof. Shavit: If that wasn’t a rhetorical question, I want to answer it. Why shouldn’t it be? Because some things in life should not be approached cynically. Because if that’s your motivation, to win the Oscars, then that’s wrong.

Prof. Lichtner: I agree. But at the same time, making a product that’s going to have broad appeal is not something that we can resent filmmakers for. So, the question is broader. Like, why is it that the Holocaust holds this special place in the public consciousness so that we flock to watch Holocaust movies, so that we immediately and somehow automatically gravitate to a film that deals with the Holocaust?

I’ll give you a different example from Italian cinema, which I think is really telling. There is a film called Unfair Competition by Ettore Scola (2001), master of Italian cinema. In it, there is a competition between two tailors, one Jewish and one Gentile, in Rome at the outset of the fascist racial laws in 1938. The scene shows how a friendly banter that was not really so friendly becomes antisemitism and racial hostility. It’s an interesting film. The most interesting thing is that when Scola drafted the idea, it was not set in 1938. It was set in contemporary Italy. The shopkeepers were a white Italian man and a recent African immigrant. Scola ultimately decided that it was safer to place it back in 1938.

Across Europe, there’s a history where the Holocaust was first the uncomfortable topic that we don’t want to deal with, and then it became the comfortable topic that we deal with instead of dealing with contemporary racism. That is the question that you have to address if you want to understand why cinema, cynically or conveniently, seeks out the Holocaust to make money or to win awards.

At the same time, just because there is this cynicism or instrumentalism, it doesn’t mean that all Holocaust cinema is cynical. It comes back to a point I think Moshe made earlier on, which is a really important, really complex point about the definition of the Holocaust. I’m not going to try, but the Holocaust is a really difficult event to define. It defies definition.

And so you have a genre: Holocaust cinema is treated as a genre. We write about it as a genre, but actually, it’s a cross-genre. I think there are Holocaust films that cut across all genres, and if you boil it down, most Holocaust films are not really about the Holocaust. They’re about other things, and that was always Benigni’s defense. He said, this isn’t a film about the Holocaust, it’s a film about the love between a father and a son, a film about the power of imagination.

Dr. Duvdevani: First of all, I think that saying that all of it is cynicism is a big generalization. I completely agree with you about Benigni’s reaction. But at least, when he got the Oscar, he never thanked the six million.

Prof. Shavit: I watched his act again yesterday. He was actually closer to thanking the six million than Spielberg was.

Dr. Duvdevani: Indeed. But you’re completely right that Spielberg actually never thanked the six million. He mentioned them in his thank you speech, but he never thanked them. Believe me, Spielberg knows what he’s doing.

Anyway, yes, there is cynicism in Holocaust movies. However, there is also cynicism when you are making a film like The Green Book (2018) about the relationship between a black pianist and his white chauffeur in the 1950s. And there is a cynicism when you are making a film like Twelve Years a Slave (2013). So, in a way, when we are dealing with the award season, cynicism is quite common.

We should bear in mind that there are many other films we have not discussed yet. For example, there is a film that we still haven’t mentioned, and I think it is a very important film: The Pianist (2002) by Roman Polanski.

Prof. Shavit: Which also, in the end, is a feel-good movie.

Dr. Duvdevani: You know, Władysław Szpilman survived, but I can’t say that when I see the way that they are clearing the ghetto and killing the Jews, I had a feel-good reaction.

Prof. Shavit: Well, you know that the experience of the audience is mainly determined by the fate of the protagonist, not what’s in the background, and in the end, if the protagonist survives and plays the piano, it’s a happy ending.

Dr. Duvdevani: But I don’t think it’s a feel-good movie. It’s a film about survival. And yes, I am very happy that he survived, but he experienced a very traumatic event.

As we speak, in half an hour, we’re going to have three hostages released from Gaza, and I’m not sure that today is a feel-good day. They survived. So, I think survival is not the point.

Prof. Shavit: Well, the media treats it as a feel-good day.

Dr. Duvdevani: Yes, so the media is wrong. What can I say? But you cannot suspect Polanski, for example, who himself was a Holocaust survivor, to have thought that he was making a feel-good movie.

By the way, in my opinion, the actual film that Roman Polanski made about the Holocaust was not The Pianist. It was a film that he made two decades earlier, The Tenant (1976), in which he himself played someone who is being persecuted. I think that this is the real film, metaphorically speaking, that he made about the Holocaust. It’s very interesting to note that in Polanski’s autobiography, he deals extensively with other films, but The Tenant is discussed only in three pages.

Going back to the question, I think we should remember that there are also European films and also American films that won the Academy Award and are really dealing with the Holocaust in a profound, harsh way.

Prof. Zuckerman: Spielberg probably didn’t talk about the six million Jews, but I remember a video that I saw from a post-award celebration, where someone came in with a real big cake, the way the Americans like it, and they had something written on the cake. What was it? Shoah.

Prof. Shavit: I can’t believe this.

Prof. Zuckerman: I saw it. I am not making this up.

I am always distinguishing between the work of art and its creator. The creator may be a bad person but still make a very important work of art, and it can be the case that a very good person will create very poor art.

So, I am not interested in what motivated Spielberg, whether his motivation was cynical or commercial. The question is: what is the structural moment within the work that is putting us into dilemmas, ethical dilemmas, aesthetical dilemmas, and moral dilemmas?

I think that most of the Holocaust movies are not able to really result in a message that is humanistic, that is going beyond the Holocaust. As I said before, the Holocaust itself is still an enigma to us. We are still not able – I am seventy-five years of age now and even I am still not able – to understand it, and as I said before, it’s been in my life from the very beginning.

We have to distinguish not only between the intention of the creator or the producer and the work of art; within the issues or topics of the artwork itself, we have to distinguish between coping with the actual historical event and the reception of the work decades later.

Prof. Shavit: I want to move on to the next and final point of criticism, which is Holocaust movies and porn. Now, there are two issues here. The first is that you have a lot of nudity in Holocaust movies, at least in some of them, especially in the ones that are more, I would say, “realistic.”

At least in my generation, for most kids, the first authorized seeing of a naked body of the opposite sex was when watching a Holocaust movie.

That’s the definition of disturbing.

The second point is that in the end, when you have those documented visuals from concentration camps, from extermination camps, and you show naked victims, identifiable naked victims, that does not dignify them. The question is, don’t they deserve the dignity of not being shown to the world like this? And when they are denied that dignity, and so casually so, is that not a statement that they are lesser humans, that we accept their being classified as such?

Dr. Duvdevani: First of all, I am not sure that most or even many Holocaust movies have nudity. And I am not sure that I would associate only Holocaust movies with nudity. I do think that there were films back in the 1970s that dealt with the Holocaust and had nudity. This was part of the provocation; they sought a way to deal with Holocaust representations and with Holocaust memory.

There are two films, both of them Italian, which I think are very interesting in this regard: Seven Beauties by Lina Wertmüller (1975) and The Night Porter by Liliana Cavani (1974). I think that these are masterpieces because they combined sheer provocation, not cynicism, with issues of representation and with issues of memory.

They are meant to disturb you. They were made by women. Women are those who usually do not take a side in history, and by this, I mean that history is not being told by women. Films were mainly made by men, especially in the 1970s. So, what I think the directors were aiming to do was to give a certain kind of a new perspective, a provocative perspective on the whole idea of masculinity.

Seven Beauties is a film about masculinity and the crisis of masculinity when dealing with the Holocaust. And in The Night Porter, sex, I mean real sex and actual sex, takes place in order to cover the trauma.

Still, I do not think nudity is part and parcel of Holocaust films. But I think in both these films, nudity was used as an issue or as an aesthetic tool to deal with the trauma and the crisis of masculinity that was caused by the Holocaust.

Prof. Lichtner: I want to draw a distinction between literal porn in movies connected with the Holocaust, a horrible sub-genre that came out in the 1970s, which I’ll leave aside, and voyeurism.

The presentation in some movies of gas chambers, in particular, is troubling. I am thinking about The Grey Zone, for instance, by Tim Blake Nelson (2001). I think it has a genuine, almost pornographic voyeurism in the shooting of the gas chamber scene where he puts you in the position of a girl following her mother into the gas chamber. Then, it has the luxury of dragging you out at the last minute. That shift of perspective is voyeuristic, it is unethical.

Back to nudity, I am thinking of the British documentary German Concentration Camps Factual Survey, which was produced by Sidney Bernstein with the help of Alfred Hitchcock in 1945, but released only in 2014 after having been shelved for seven decades. By the way, aside from technical issues and the fear of alienating the German-occupied population, one possible reason why it was originally shelved by the British was their fear that it would help the Zionist movement.

When it was eventually completed and released in 2014, the Imperial War Museum curated it and took it to Sydney and various other places to premiere it. In Sydney, the curators were challenged about the way that the cameramen deployed in 1945 by the British military were shooting women showering, without any sense of decency. I mean, they just shot them in frontal nudity.

And the curators responded, well, these are French Jewish survivors who were showering with hot water for the first time after God knows how long. It’s about hygiene. It’s about the return to humanity. And the audience challenged this, saying, these women did not consent. It is their body. So, I think that even in something that’s not fictional, nudity is an immediate dilemma.

Prof. Shavit: Even more so when it’s not fiction.

Prof. Lichtner: Yes, you’re absolutely right. In the same footage, but not included in the film, there’s a different kind of approach to pornography, though not with respect to nudity, but with respect to death. There’s a moment quite late in the liberation of Belsen when the army film unit sent footage with notes to London saying that today, the commanders decided to use the bulldozers to scoop up the corpses and put them in the graves.

This is a really poignant moment, and they film it. But they can’t film it close up, so they put the camera behind two survivors who were watching a British Sergeant on a bulldozer scooping up bodies. You can just see the bodies falling out and going underneath the bulldozer itself. Yet you see it out of focus because the thing that’s in focus is the shoulders of the two women watching it. That’s the same technique that László Nemes used in Son of Saul.

Prof. Zuckerman: The question of the Holocaust and nudity stirred a little political crisis in Israel some 20, 25 years ago when an ultra-Orthodox politician toured Yad Vashem and said about one of the biggest photos, which was, of course, the naked women on the way to their extermination, that this was unacceptable. And then he said, we need our own Yad Vashem. This ultra-Orthodox politician said we need our own Yad Vashem; your Yad Vashem cannot be ours.

The question is, what kind of gaze, or what kind of view, does this Haredi politician have when he recognizes in this naked woman something erotic or something sexual? And so on. But he related to it quite clearly, quite well, when asking: “If it were your grandmother, how would you react to the photo?”

Well, if you want to be a good historian, you have to admit that there are moments in history where pornography being the pornography of death, being the pornography of eroticism, being the pornography of the sheer reality of being, is part of everyday life.

If I may add something here that has nothing to do with sex and nudity. My father remembered a scene that he had experienced in Auschwitz, and there, of course, we lost a major part of our family, some 80% were exterminated, but he remembered that he was in some kind of hole where he was working. There was some sort of assessor who came and saw my father, and all of a sudden, he flung him a bun. And my father, who was not able to speak about the Germans without saying, “May they all burn,” remembered that. He remembered this moment as something, some kind of glimmer of humanity even in this hell. Even the assessment man had this humanistic moment when throwing him the bun.

I think the need to combine the Holocaust with sexuality, and I’m not talking about nudity, comes from the place where you need to have something to hold on to because if you are showing all the time only the everywhere presence of death, you cannot do anything with it. Not intellectually and not artistically, and certainly not cinematically.

Prof. Shavit: Certain B movies, where you have concentration camps with women enslaving a man or the other way around, their production is actually revealing something very deep about the Holocaust itself: that there were people taking pleasure in doing all those things. And that there are now people taking pleasure in watching people who took pleasure in doing all those things is part of the story of the Holocaust. It helps us understand how it could have happened.

So perhaps in an awkward way, we learn more about human nature through those distorted B movies than through mainstream and legitimate movies.

Just as a final point, there was a period, I think it was like 20 years ago, when the London Dungeon and these kinds of facilities were very popular. They featured all sorts of terrible medieval torture instruments and epidemics and other catastrophes.

I remember hearing someone asking whether they would have a Holocaust dungeon in 500 years and will people treat it as some kind of entertainment. Because, in the end, what we were entertained by when going to the London Dungeon was people being tortured. And tormented.

I would like to move on to asking the three of you three different questions about different countries and Holocaust movies.

I want to start with Moshe and discuss two major German films, which I am sure you’ve watched. One is Der Untergang (2004) and the other is Napola (2004). What I found very disturbing in both is the narrative of the Nazis as some kind of aliens that came to Germany from outer space and took over until they were defeated. How troubling did you find this when you watched either?

Prof. Zuckerman: Yes, I was troubled that a certain part of coping with the past in Germany was exactly like what you said.

There were a few paths to deal with the history of Nazism. The first one was Germans who said that they were kidnapped by a bunch of criminals. And it was what is known in German as “the twelve years of Hitler. ” How 80 million people could be kidnapped by a bunch of these people is another question, but it was very soon that the post-war Germans didn’t go on with that.

Another way of coping was to focus on the German opposition to Hitler, the opposition that collapsed.

The third way, which started in the 1980s, was to engross with everyday life Nazism. Maybe you remember the series of films Heimat by Edgar Reitz (starting in 1984). It was very interesting to see in those films how Nazism infiltrated into remote villages and how it became a part of them.

So, in that respect, Der Untergang, in which Hitler is shown as a psychopath – and he was very ill at the end, and we can, of course, make a caricature of him, and I’m not saying Bruno Ganz’s performance as Hitler was bad; his performance was excellent – but that film was indeed some kind of escape from the real question. The real question is not how Hitler was at the end, but how could it be that until the very end, there hardly was any opposition to Hitler.

Prof. Shavit: Hitler is so external to the reality of the ordinary Germans in that movie.

Prof. Zuckerman: This is exactly what I am talking about. This is a way of not coping with your own guilt when you are showing him as something coming from somewhere else. Having said that, I have to admit that the one country that tried to cope with this past in Europe, when I compare it to the way that the British and the French cope with their colonial past –

Prof. Shavit: Or the Dutch with their Nazi past.

Prof. Zuckerman: Yes, or the Dutch with their Nazi past, and the Dutch with the colonial past as well.

Prof. Shavit: The Italians with their fascist past. But I would not compare the Nazi past to colonialism.

Prof. Zuckerman: The one country that did some kind of work of coping with the past is Germany. The question was, what path did they take? And they took, as I just tried to show it, several paths.

I think that by the end of the 1960s and 1970s, the Germans began to reflect on fascism more seriously. But, and this is a big but, they ended up with a very good explanation for fascism and even for Nazism, but not for the Holocaust. They basically concluded that they cannot cope with the Holocaust, neither historiographically nor through cinematographic works.

And in that respect, the Germans are in the same situation as others. I don’t think that others can cope better than the Germans. The Germans used to think that the only ones who were really pure and clean and without any crimes were those serving in the Wehrmacht. And then, it turned out that the Wehrmacht was one of the major promoters of war crimes against the Jews.

I think that the problem is that the Germans had a special problem coping with the Holocaust because these were, as the Polish Government rightly said, these were German concentration camps. Although Ukrainians, Poles, and so on collaborated, the concentration camps were German.

Prof. Shavit: Giacomo, my question for you is about perhaps the most contentious debate when it comes to Holocaust movies, which you have already referred to and somewhat hinted at where you stand, but I’m not sure I understood correctly. We are twenty years after that debate, so there is a bit of the benefit of retrospect or at least of a broader, longer perspective. Roberto Benigni and Life is Beautiful. Where do you stand in this debate?

Prof. Lichtner: I feel like I’ve made a career out of criticizing Life is Beautiful. I was an undergraduate when I first saw it, and I kept watching it, and each time I watched it, I liked it less. But I do remember the first time I saw it in the cinema at Christmas. Life is Beautiful was a Christmas release. And the posters advertising it showed Benigni and his wife, who’s also his on-screen wife, Nicoletta Braschi, smiling on a beautiful navy blue background with snowflakes falling.

I remember being really struck by the catharsis at the end of the movie, being moved, crying, and then each time I watched it, I liked it less.

Prof. Shavit: Why?

Prof. Lichtner: Because I think the second half is so false. You know, it’s not just inaccurate; it’s false. It’s entirely driven by the motivation of providing catharsis.

The first half is actually quite brave. It is brave because it breaks a big silence. The big silence in Italian culture is not antisemitism and the Holocaust. That’s something Italians, in the end, deal with quite easily because they just blame the Germans for it.

The big silence is Africa and what we Italians did in Ethiopia and in the other African colonies before the war. And Benigni has a way in that first half of the movie of criticizing fascist culture very subtly, including with things like the Ethiopian-themed party and so on.

There’s a critique of homemade antisemitism in the racial laws that’s actually rare in Italian cinema. The only other noticeable example I can think of is maybe Vittorio De Sica’s film The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1970), which acknowledged that Italy passed racially discriminating laws by itself well before the Second World War started, before Hitler demanded that they do so.

So, the first half of Life is Beautiful is quite brave, and the second half falls on its own premise. Benigni wants to carry on with this idea that life is beautiful, but once you take the characters into the concentration camp, it is, in my opinion, simply not possible anymore to keep that narrative going.

Prof. Shavit: Your criticism of that movie – how far will you take it? Will you say this is a movie that people should not watch, or will you say this is an effort that failed?

Prof. Lichtner: I think it’s an effort that failed. There are very few movies that I think people shouldn’t watch. Maybe Uwe Boll’s Auschwitz (2011), which was actually banned in Germany and is hard to get a hold of. Maybe that and then just a few others.

No, I definitely wouldn’t censor Life is Beautiful. I just think it’s an effort that failed, partly because Benigni is good at talking about what he knows about, which is not the Holocaust.

There’s a fantastic work by Ruth Ben-Ghiat about the film, where she says, look, forget about the Holocaust. The film is about Italy. The catharsis is the catharsis of Italy being liberated by the Americans.

And this is what infuriated some historians about the movie, the idea that Italian Jews go to this imaginary camp and then are liberated by the Americans instead of the Russians. It infuriated historians because Italian Jews, for the most part, including my grandfather, his mom, and his brother – they were all in Auschwitz – they were liberated by the Soviets. Mind you, Benigni’s father was imprisoned in Bergen-Belsen, which was not liberated by the Soviets. It was liberated by the British.

Prof. Shavit: Going back to the cynicism, however, it’s not an effort that failed from Benigni’s point of view. He won the Oscar that he wanted to win.

Prof. Lichtner: From his point of view, he did it well. I think it fails because it doesn’t understand the essential elements of the history of the Shoah, the things that Moshe was talking about at the beginning: the systematic nature, the industrial nature, and the modernity of the Holocaust as a standalone event. He doesn’t understand that. How could he?

Prof. Shavit: I want to ask Shmulik about Israeli cinema now. In 2024, four major Israeli movies were released about the memory of the Holocaust; about how you deal with the memory of the Holocaust. Four! But not about the Holocaust itself.

And then, I look at the list of movies that have been produced since 1948, and there are hardly any Israel-produced films about the actual Holocaust. How do you explain that? In other words, why are there so few movies about the Holocaust, as opposed to the memory of the Holocaust?

Dr. Duvdevani: I think that there are three reasons why there were so few Israeli films that actually dealt with the Holocaust itself.

First, asking Israeli actors to play again the role of the victims and especially maybe asking Israeli actors to play Nazis, was difficult.

Second, Israeli cinema, at least in its early years, referred to the trauma of Holocaust survivors as one that can be remedied through fresher traumas, which were the focus of its attention.

The third problem is political; what analogies, whether ill-intended or not, will people draw from direct depictions of the Holocaust? Some Israeli moviemakers were reluctant to deal with the Holocaust directly because they feared the response of their peers in other countries, at least subconsciously.

Prof. Shavit: There was perhaps a technical impediment, which is, you know, you need access to certain sceneries if you want to adapt the novels of, say, Aharon Appelfeld to the big screen.

Dr. Duvdevani: Well, I know about at least one Israeli film that is being made at the moment in Yiddish and is being shot, I am not sure where; they wanted to shoot it in Ukraine, but it’s not shot there. And it’s actually a film dealing with the Holocaust.

Prof. Zuckerman: I think that there are no Israeli movies dealing directly with the Holocaust, but only with the memory of the Holocaust, because Israel, whatever the public opinion is, was never interested in the Holocaust. Israelis were always very interested only in the memory of the Holocaust as part of the ideologization of the Holocaust, in terms of Zionism being the solution and being the answer to the Holocaust. This is why, by the way, we don’t have proper research on antisemitism.

I’m thinking about research, proper research on antisemitism in terms of social, psychological, economic, and other aspects.

Prof. Shavit: Well, you know, Moshe, as someone who has dealt so much with memory and with history, you know that history is a work in progress. In the end, people learn history to justify the present and the future.

And now, very final questions calling for short answers. Shmulik, did The Brutalist deserve the Oscar for best movie it didn’t get?

Disclosure: I wish I thought this movie is bad. It is not, I thought worse of it. It’s banal; it does not say anything new or interesting about any of the complicated topics it broaches. As a commentary about the roots of American decline, it manifests the decline in not being able to add something inspiring to the discussion. Sorry for the Spenglerian tone. Anyhow, do you think it deserved the Oscar?

Dr. Duvdevani: Yes.

Prof. Shavit: Why?

Dr. Duvdevani: Because I think it is major movie making. It is a very long epic, though a very intimate epic, about antisemitism, Zionism, memory, architecture, and capitalism, and it deals with all these complicated issues creatively, coherently, and with much substance.

Prof. Shavit: Moshe, if a German high school teacher told you he could show his class, let’s say of 12th graders, just one movie about the Holocaust, which would you recommend?

Prof. Zuckerman: I would recommend Lanzmann’s Shoah in a shorter version. You don’t need the whole eight hours, but in a shorter version, I would recommend it.

Prof. Shavit: You’re optimistic that high school students today can deal even with a shorter version.

Prof. Zuckerman: No, I’m not optimistic at all. You asked me what I’d recommend, not what could actually work.

Prof. Shavit: Giacomo, same question but for New Zealand high school students.

Prof. Lichtner: High school students? I mean, the smart answer is Jojo Rabbit (2019).

Prof. Shavit: Why is that your recommendation?

Prof. Lichtner: Because it’s a New Zealand film by director Taika Waititi, who’s half-Māori, half-Jewish. He made Boy (2010) for his Māori father. He made Jojo Rabbit for his Jewish mother, and it’s a film that is obviously, evidently fantastical, so you don’t have to deal so much with the fear of people coming out of it thinking they understand the Holocaust now. It’s approachable.

Prof. Shavit: And for Italian high school students, will the recommendation be the same?

Prof. Lichtner: No, for Italian students, I would probably get them to watch Kapo by Gillo Pontecorvo, which was made in 1960. This movie is so important to the history of the representation of the Holocaust in cinema. The way it approaches certain imagery – the barbed wire, for instance, became a trope that then got quoted over and over again in Holocaust movies.

I think that in this movie you can see a Jewish prayer in Hebrew for the first time in the history of Italian cinema. At least, it is one of the first times. The Shema are not quite the final words in the movie, but are the final words of the protagonist. And then she dies. It is quite a powerful film. Problematic in all sorts of ways, but powerful.

Prof. Shavit: Why would you offer New Zealander and Italian high school pupils different movies?

Prof. Lichtner: Well, they need to learn different things.

- With contribution from Amarah Friedman